Exterior of Campus Cruiser office.

On a Thursday night in September, USC student Rachel Scott walked off campus toward the neighborhood west of Vermont Avenue. Normally, she would have called Campus Cruiser to take her there, but this time she decided to bypass the wait. Previous experience had her waiting 20 minutes on hold or for a car. It was still before 8 p.m., early enough for her to walk alone safely.

Or so she thought.

When Scott reached the Taco Bell on Vermont Avenue and 36th Place, a group of men surrounded her, catcalling. She said that a campus security officer stationed nearby failed to intervene. Luckily, after a few minutes, the men went away. But Scott said the fear remained, forcing her to rely on Campus Cruiser, even when it was plagued by delays. “I would rather wait to get dropped off than walk on the street,” she said.

Scott is one of several students who say that this semester, unusually long wait times - on the phone or for a cruiser - have forced them to seek alternatives, sometimes risky ones, to get off campus at night. In the two months after President C.L. Max Nikias announced that Campus Cruiser wait times would be no more than 15 minutes, the program has experienced many setbacks in trying to fulfill this promise.

Last year, Campus Cruiser employed 125 drivers and had 30 cars in its fleet. They dealt with an average volume of around 600 calls a day. This fall, volume has approached 900 calls a day and has even climbed to over 1000 calls on Thursday, Friday and Saturday, when more students go out around campus.

Tony Mazza, Director of USC Transportation, which oversees Campus Cruiser, cited three factors that have caused demand to skyrocket: an extension of service boundaries, and an increased concern for safety after the murder of international student Xinran Ji, coupled with the promise to limit wait times for a car to 15 minutes. This has forced program management to increase the number of drivers from 125 to 154, increase the number of cars from 30 to 43, install a new phone system and two new dispatching stations, reduce training times for new drivers and employ other measures in order to deal with the increased volume.

This has also created many inconveniences for students. A variety of Campus Cruiser passengers, employees and USC transportation and public officials have expressed how they’re dealing with these changes and why they came about in the first place.

Read More: Phoenix Tso's "Campus Cruiser Video Diary" here.

The Border

DPS patrols response area with state-of-the-art cameras.

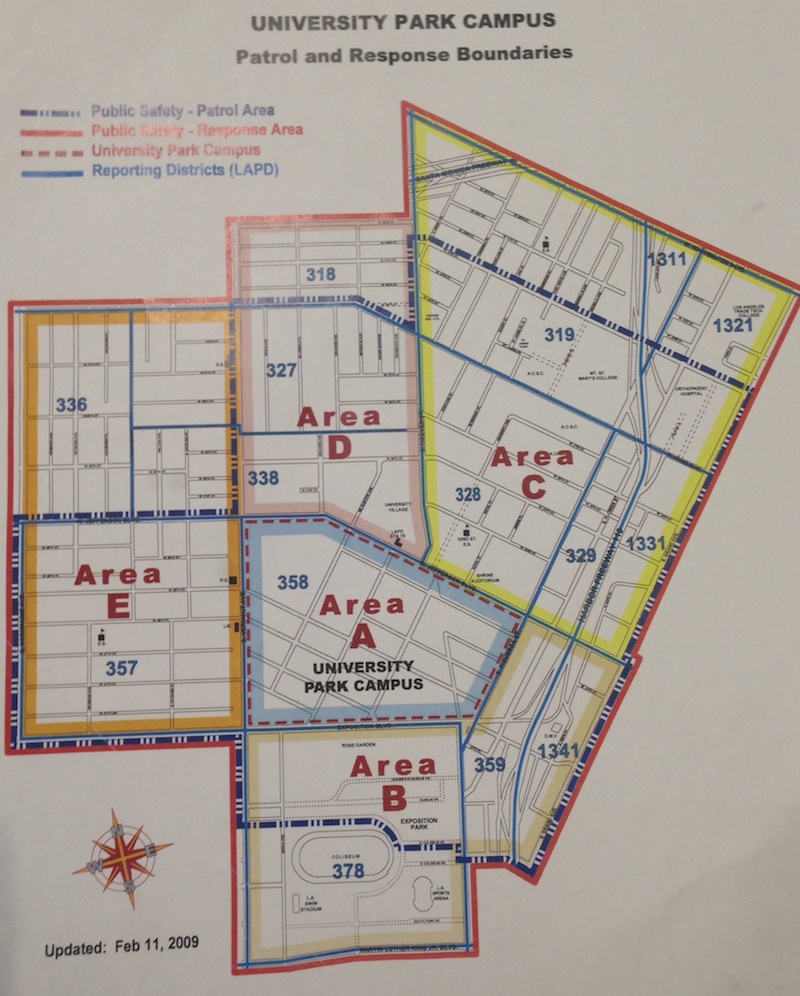

For the last decade or so, the USC Department of Public Safety (DPS) has patrolled the University Park campus and its surrounding neighborhood using two sets of boundaries. “[The interior] border defined where we would receive calls, and the [exterior] border was a patrol border where we would [actually] patrol,” John Thomas, the Chief and Executive Director of Public Safety, said.

DPS would also respond to calls in the area between the interior and exterior border, rendering the interior border effectively useless for their operations. Yet because this boundary denoted their official service area, as written in their memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the LAPD, Campus Cruiser’s operations were limited to the interior border.

For students, these two borders caused confusion and misgivings about safety, said Chief Thomas. “We had students living outside the [interior] border,” he said. “And Campus Cruiser would take you right here, and say, ‘I can’t go any further.’ ”

A map of DPS response and patrol boundaries. As of April 21, 2014, the DPS official patrol area has extended from the boundary denoted by the blue dashed line to the red line. Photo courtesy of USC Department of Public Safety.

In 2012, two Chinese international students were murdered in the area north of Jefferson Boulevard and west of Vermont Avenue, which lay outside DPS and Campus Cruiser’s official service area. This prompted the LAPD to expand their patrols there, but not to expand the official boundary for themselves or Campus Cruiser. A year later, a Neon Tommy op-ed quoted Chinese student Fei Zeng as saying, “ ‘I know some friends who live a little bit far away from the campus, like out of the safety zone. Sometimes they have to get home late. If the cruiser could go further, that would be much safer for them.’ ”

Chief Thomas, who was appointed to the head of DPS in January 2013, said that officially expanding the boundary was probably a priority for his predecessor, but not to the extent that it was for Thomas himself, since he worked for the LAPD and had grown up around USC. “From the LAPD officer standpoint, [having the interior boundary] didn’t make sense, from DPS standpoint it didn’t make sense, and most importantly, from the student standpoint it didn’t make sense,” he said. “So it was a no brainer.”

At the end of 2013, DPS began negotiations with the LAPD and the Los Angeles City Attorney’s office to amend the MOU and officially extend the border. On April 21, 2014, the amendment went into effect. Campus Cruiser could now extend their service area to the exterior boundary.

The Ramp Up

By June, Campus Cruiser was planning to increase the number of drivers and cars in order to accommodate the boundary expansion. They had also seen a significant increase in call volume during the last few weeks of the spring semester, similar to the nightly call volume Campus Cruiser currently experiences, according to their program call logs.

“Our wait times were definitely above 15 minutes,” Michelle Garcia, Associate Director of Guest Relations at USC Transportation, said. “On Thursday, Friday and Saturday they’d go up to 30 minutes.”

Some students agreed. “I had to wait forever for a cruiser in the spring,” Alexa Liacko, a senior at USC, said.

However, the summer decrease in students on campus made it hard for Campus Cruiser to recruit new drivers, according to Director Mazza, as well as determine if the increase in demand would stick.“The summer numbers [this year] were the same as last summer,” said Garcia. She added that during this season, calls would only average around 200 a night.

As a result, program officials wanted to monitor demand in the fall, while gradually hiring new drivers for a boundary expansion slated for spring 2015. “We were asked to do so in September instead,” Mazza said. “It’s not what we thought it was going to be.”

Everything changed when Xinran Ji was killed at 12:45 a.m. on July 24, 2014, just north of campus. Although crime around USC is low, according to the school’s Clery statistics, this incident renewed safety concerns that had arisen with the double murder two years ago. In the aftermath of Ji’s death, Chinese and other international students met with administrators four times in late July and August.

During these meetings, they voiced their concerns about campus safety, as well as their frustration over what they saw as the administration’s blasé attitude towards Ji’s death. For example, they criticized Provost Elizabeth Garrett’s campus-wide letter characterizing his murder as an “isolated incident,” and the unqualified interpreter USC hired for Xinran Ji’s memorial service, as Yuanzi Xie, co-president of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), which was instrumental in negotiating new safety measures, said.

“As for the campus cruiser, that’s where more people complained, because of the response time,” Xie said. “For them, the attitude might not matter much, but the actual response and action will matter more. Cause there have been cases where they didn’t even come.”

As a result, on July 28, senior administrators asked USC Transportation to come up with a plan to extend boundaries and reduce wait times right at the start of the fall semester. On Aug. 19, the first day of operations for the academic year, management informed the returning drivers of the change. “It happened very quickly from ‘it's coming’ to ‘no, it's today,’ ” Garcia said.

The Effect

To deal with renewed safety concerns and sudden policy changes, Campus Cruiser used the spring 2014 demand increase as a template for the fall ramp up. “We anticipated that the number of calls would probably increase by about 20 percent or so,” Director Mazza said. So far this semester, that increase has actually reached 34 percent, though not because of the new service area, apparently.

“The number of calls we get in the response area was not what we thought it would be,” Mazza said. “That’s not the number that’s driving the increase. It’s part of it, but it’s just it’s more associated with the fact that students are just more aware of [Campus Cruiser].”

Whatever the reason, the increase in calls has been astronomical. “I’ve never worked a night before where call volume went over 1000 calls,” Kaelah Gildea, Assistant Manager at Campus Cruiser, who has worked for the program for almost five years, said. “All of our non-peak hours are becoming peak hours, and the peak hours are becoming super duper peak hours.”

Campus Cruiser had to quickly find new drivers to keep up with the demand. “This was already difficult, but now we had a higher target [of 154] to hire too,” Associate Director Michelle Garcia said. She also said that the first chance that Campus Cruiser had to recruit new students was during the USC Job Fair on Aug. 22. This year, according to Mazza, they hired 50 students on the spot, then recruited the remainder during the semester, cutting their training from five days to one in order to get them integrated as quickly as possible.

According to Raoul*, a driver, trainer and dispatcher for Campus Cruiser, this has meant teaching new drivers the essential addresses, radio codes and other procedures and then having them pick up the rest through experience. “Especially with the new boundaries, you can’t learn everything within four hours,” he said. “Still, people usually do pretty well within a couple of weeks.”

“I’ve never really had to give directions,” Brinda Sreedhar, a first-year graduate student, said. “I haven’t been able to identify which ones are the new drivers and which ones are old. That’s a good thing.”

The real challenge is the high driver turnover, a regular feature of Campus Cruiser. “We have about a 10 percent attrition rate in Campus Cruisers,” Mazza said, “So we’re constantly hiring to keep up with people who might be leaving because, you know, the job wasn’t what they thought it was or they have some other priorities.”

This year, according to Gildea and John Zajac, Manager of Campus Cruiser, despite the fact that this program has hired way more bodies, a good amount of those students don’t want to tie themselves down and leave, which has made it difficult for Campus Cruiser to maintain a full staff to keep up with this year’s demand.

In addition to hiring enough drivers, Campus Cruiser has also struggled with decreasing their call waiting times. “I call in a half hour beforehand, because of waiting time on call and for the cruiser,” Sreedhar said.

The Campus Cruiser fleet.

Alexa Liacko has had a similar experience on the phone. “On a Thursday, Friday or Saturday, I’d often be on hold for 20 minutes, and then they’d tell me the wait is 20 minutes,” she said. “I usually take Uber on those days instead.” Other students have said that they often get a busy signal after waiting on hold for a few minutes, giving them no choice but to redial Campus Cruiser’s number until they get through.

At any given time of night, Campus Cruiser usually has only three dispatchers on duty, which creates a bottleneck. “Even if they have 20-30 drivers out on the road, there’s nothing you can do about [the call waiting times], if you have only three people in the office receiving all these calls,” Raoul said. In order to fix this, Campus Cruiser upgraded their phone system in mid-September, Michelle Garcia said, so that five dispatchers can work at one time, and so that students can request a call back from a dispatcher instead of having to wait. While there are still usually only three dispatchers, supervisors often monitor for how long callers are placed on hold, with Gildea getting notifications if those times exceed five minutes. “In those cases, I’ll often fill in as the fourth dispatcher to get those times down,” she said.

Since the new phone system went live, dispatchers picked up 7100 calls with three minutes. The average call waiting time is now 2 minutes and 48 seconds. Despite this, however, Rachel Scott and some other students are still reporting long wait times and dropped calls, usually during the weekend.

The Future

As these issues persist, Campus Cruiser personnel continue to look at ways to improve service. “There’s still a significant number of people being picked up outside of that 15 minutes,” Mazza said. “Michelle and I talk constantly about additional resources to do that.”

As a result, Mazza and Garcia are asking for a budget increase in order to add 22 drivers and to purchase additional cars and equipment to the 13 vehicles they’ve already bought. In August, Transportation asked for and got a $500,000 increase over their $1.5 million budget to hire up to 154 drivers and to buy 13 new vehicles and other equipment.

In addition to the call-back feature, Campus Cruiser has implemented an online operator from Sunday through Wednesday, and is looking into other technology solutions to reduce wait times. Among the possibilities is providing “Uber-like technology” for people to track their cruiser on their phone, Mazza said. Transportation is also considering a deal to have Uber drivers stationed near campus to help Campus Cruiser drivers during peak hours.

There’s also a question about whether improvements will extend to summer. After Xinran Ji’s death, Yuanzi Xie and the Chinese Students and Scholars Association asked for USC to extend Campus Cruiser summer hours, which are from 6 p.m. to 12:45 a.m. to the same hours as the academic year, until 2:45 a.m.

“I wouldn’t anticipate that the hours would change during the summer time,” Mazza said. However, he also added that they could be extended if the need arose closer to the summer months.

Until then, Campus Cruiser continues to deal with staff turnover and call volume increases. “The only thing I feel bad about is that I don’t want to deceive the students. Because there’s that idea that now we’re supposed to guarantee those [15 minutes wait] times, when we actually can’t at this point,” Raoul said. “Maybe in the future, but just with the high volume of calls we receive these days, it’s just impossible to meet that, especially on the weekends when everybody is out.”

Perhaps this will always be an issue for Campus Cruiser. “What we’ve noticed over the last six or seven years is that as we drive the wait times down by adding new resources to the program, then the popularity of the program continues to increase,” Director Mazza said. “We find that we’re constantly chasing a number.”

*Name has been changed.

All photos by Phoenix Tso unless otherwise noted.